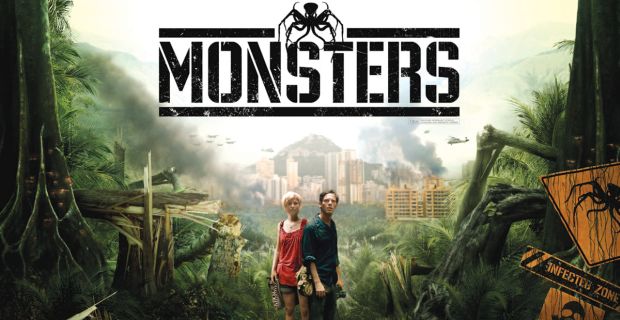

When Gareth Edwards‘ stunning Monsters debuted at SXSW in 2010, few could have anticipated that the British director would be helming the reboot of Godzilla inside a few years. It’s something of a leap from indie sci-fi to the greatest creature franchise in cinematic history, but no one who saw Monsters could have doubted Legendary’s choice. Edwards’ vision and craftsmanship was already abundantly clear from this first feature, a little-known but stirringly accomplished work that ranks among the finest debuts of our time.

On the face of it, Monsters is about an alien invasion, but it’s more accurately a road movie – a literal and figurative journey through wonderment and discovery. It focuses on the fallout from the evolution of extraterrestrials in Mexico. The creatures are huge, tentacled beings but they actually barely feature in the film, becoming more background players in a distinctly human story about survival and companionship. The northern half of Mexico has been quarantined in so-called “Infected Zones” and a colossal wall has been built to fortify the boundary with the U.S.. In the midst of all this we meet Andrew (Scoot McNairy), a photojournalist tasked with escorting his boss’s daughter Samantha (Whitney Able) back to the States. However, the journey becomes complicated when the two learn that the border will soon be closed for six months and then their passports and tickets are stolen, forcing them to travel through an Infected Zone.

What unfolds is a film of haunting grace and beguiling sensitivity. Some may have dismissed Monsters on release – unfairly – for its languid pace and pensive narrative but to do so is to miss the entire point of the picture. It’s not about militaristic showdowns with the creatures or governmental attempts to deal with their encumbrance. It’s one which seeks to provoke thought and contemplation, studying the impact of a cataclysmic event on ordinary people and discerning poetry amidst their plight. It’s not uncommon for disaster movies to emphasise kinship and love, but the gentle, affecting way in which Monsters relates its story sets it profoundly apart.

The film deliberately roots itself in a disadvantaged part of the world, eschewing the archetypal urban stronghold for rural abandonment and isolation. When the governments of the U.S. and Mexico draw up the borders of the Infected Zone, they largely abandon the people living within them, casting them adrift in an unnerving inertia where wrecked airplanes and ships litter the countryside and every creak in the woods takes on a glimmer of doom. There’s no refuge or shelter for those who found a demarcation line set right through their village, and the film is forthright in evincing the graphic horror of leaving a population to eke out an existence on the fringes of monster territory. In one telling incident, Andrew – who had earlier remarked that a photo of a child killed by the creatures would be worth a fortune – stumbles across the body of a little girl who died in an attack, and hesitates before draping his coat over her remains. Such a moment could be read as allegorical, a reference to all-too-real dangers faced by people in developing parts of the world as they face down the fallout from Western greed. However, this would be to burden the film with a heavyhanded social commentary when in many ways, it’s far more affecting for its simplicity.

The story may be fictional, but its embracing of the lives affected by its events is absolute. For many in the film, the monsters are a storied horror related through television screens, but as Andrew and Samantha journey through the hulking woods of the Infected Zone we feel their presence very vividly. Much of the power in Edwards’ film lies in suggestion, as a great hulking menace seems to hang over the sprawl of forest, shore, and open ground. The landscape is battered but terrifying, the knowledge that feral creatures may tread just beyond the foliage or horizon cloaking it in awe and a newfound imperious power. The implication may be that mankind’s mastery over our surroundings is at once fleeting and illusory (a theme that would seem to extend to the upcoming Godzilla) but here it lends the film an atmospheric wonder more stirring than any prolonged show of might or ferocity.

Life in the Infected Zones seems all the more precious for its fragility, its proximity to something miraculous and severe. The people Andrew and Samantha meet show them tremendous generosity despite their afflictions, speaking to a sense of companionship that may be at the heart of what Monsters is all about. Neither Andrew nor Samantha are particularly likeable characters – he’s arrogant and cynical, she’s complacent – but as we watch them forge on in this incredible journey, visibly altered by what they see and who they meet, we share in a truly intimate and affecting love story and one which speaks not just to their characters but that of the creatures. Without giving too much away, the film’s denouement comes with a twist and it’s one which depicts the beings as lovers, not villains. After earlier fleeting glimpses have depicted them as destructive and aggressive, they are in the end illuminated against a blackened sky to appear playful, affectionate, and even tender; their interactions mirrored in those of Samantha and Andrew on the ground. That even the creatures themselves are afforded depth speaks to Monsters‘ astonishing power, as it doesn’t just show but convinces us of the vastness and beauty and vulnerability of a world permanently altered. It makes us feel as potently as it makes us think.

Edwards achieved this extraordinary feat with a crew of roughly seven people, a partially improvised script, special effects software bought off the shelf and a budget of roughly $500,000. Its quality is testament to the possibility of film, representing a uniquely coherent and compelling vision realised with the most basic of tools. The sheer unlikeliness of its creation almost adds to the allure of Monsters, a snapshot of people coming together to achieve something meaningful despite the harshness of their environment. Within a few days we’ll see what Edwards can achieve with the might of Legendary and Warner Bros. at his back, but before then, you would do well to acquaint yourself with an example of bold, stirring, visionary filmmaking at its most rare and profound.

Written by Grace Duffy

- David Fincher’s ‘Gone Girl’ Gets An Icy New Trailer - July 7, 2014

- SCENE & HEARD: ‘Jersey Boys’ - June 27, 2014

- MOVIE REVIEW: ‘Snowpiercer’ - June 21, 2014